Has British Columbia Shown the Way?

- Stacey Davis

- Dec 4, 2012

- 3 min read

As we look for safe ways to descend the fiscal cliff that will minimize harm to the economy, a carbon tax offers one possibility to raise revenues that could prevent an increase in income taxes or dire cuts in safety net programs. Integrated into a broader tax package of tax reform, a carbon price can also facilitate reductions in marginal tax rates. The western Canadian province of British Columbia offers one example of a well-designed revenue-neutral carbon tax. The carbon price, now integral to the economics of the province, represents $1.3 billion (Canadian) of a $35 billion annual budget.

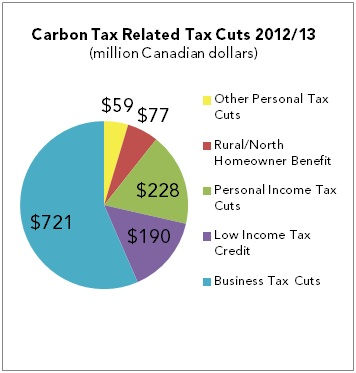

In 2008, British Columbia established a revenue-neutral carbon tax, starting at $10 per metric ton and rising to $30 per metric ton over five years. The tax gained broad support primarily based on its economic benefits; (controlled by the Ministry of Finance, the tax is not linked to BC’s GHG mitigation targets, which are the responsibility of the Ministry of Environment) the majority of revenues are used to lower business taxes (55 percent of revenues)—resulting in the lowest business tax rate in the OECD—and personal income taxes (18 percent of revenues)—resulting in the lowest individual tax rates in Canada. In British Columbia, corporations generally receive more back in tax savings than the carbon tax paid (and therefore were not vocal about the tax shift), whereas individuals generally pay more in carbon tax than the value of their income tax savings. Additionally, a portion of the carbon tax revenues were directed to rural interests and low income households to offset disproportionate reliance on transportation fuels and compensate for the regressive nature of the tax.

Besides the economic benefit to corporate interests (and to certain households)—program elements that are potentially replicable here in the US—creation of the carbon tax in British Columbia was facilitated by its parliamentary political structure, in which the party in power can put forward legislation and pass it alone; significant climate-related damage to pine forests (and forest industries) across the province; the limited share of fossil-fired power generation; and relatively small share of heavy industries. (The Province has aluminum smelting, refining, cement and forestry.)

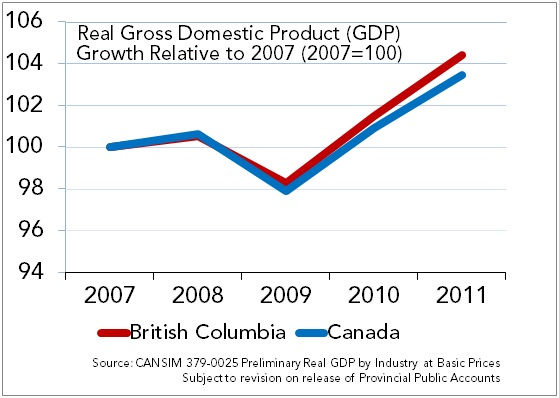

The tax has resulted in improvements consistent with moving to a low carbon economy, including reductions in use of fossil fuels (gasoline, diesel, oil and natural gas) relative to the country as a whole. Additionally, there has been 48 percent growth in the clean technology sector, and emissions reductions are on track to meet the province’s targets. At the same time, the BC economy has been growing at a faster rate than that of Canada as a whole.

The carbon tax program is currently undergoing a comprehensive review, and it is likely the design will be modified to address competitiveness concerns raised by the cement and refining sectors and to provide price certainty. Import competition (with facilities in Washington State that are not subject to a carbon price) has been an issue for the cement sector. The BC government is evaluating options to limit impacts on the competitiveness of these industries. As a province, BC does not have the option to enact border adjustments. Instead, BC is looking at ways to tax the product (e.g., through the cement blender) rather than the carbon content of the fuels purchased, so that cement imports would be treated equally to cement produced domestically. Additionally, modifications are needed to provide certainty on future carbon tax rates beyond the next two years.

Additional information on the British Columbia carbon tax can be found in a presentation, delivered by Tim Lesiuk, Executive Director, Business Development and Chief Negotiator of the Climate Action Secretariat, Province of British Columbia, to the various industry, labor, environmental group, think tank and government representatives participating in CCAP’s October 2012 Climate Policy Initiative dialogue meeting.

Comments