Opportunities for Sustainable Development within the Waste Sector

- CCAP

- Oct 15, 2012

- 3 min read

As CCAP’s MAIN program progresses, exploring possible policy options and strategies within the nationally appropriate mitigation action (NAMA) framework that curb emissions and promote sustainable development is essential. The waste sector specifically presents a myriad of mitigation opportunities, many of which focus on reducing methane released during the disposal process. Methane, or CH4, is a particularly potent greenhouse gas with 25 times the warming potential as CO2.

With the MAIN initiative well underway in Latin America, CCAP is working with local officials and key stakeholders in participating countries to implement policies bolstered by the NAMA framework that reduce greenhouse gas emissions within the waste sector.

In Latin America, methane emissions from solid waste disposal are projected to increase about 18 percent (from 2005 levels) by 2020, and only 23 percent of collected waste is disposed of in sanitary landfills. While the waste sector in most developed countries accounts for only between 2 and 3 percent of total emissions, waste sector emission from the eight MAIN-Latin American countries that work with CCAP – Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Panama, Peru and Uruguay – range between 3 and 15 percent (averaging to 6 percent) of total emissions.

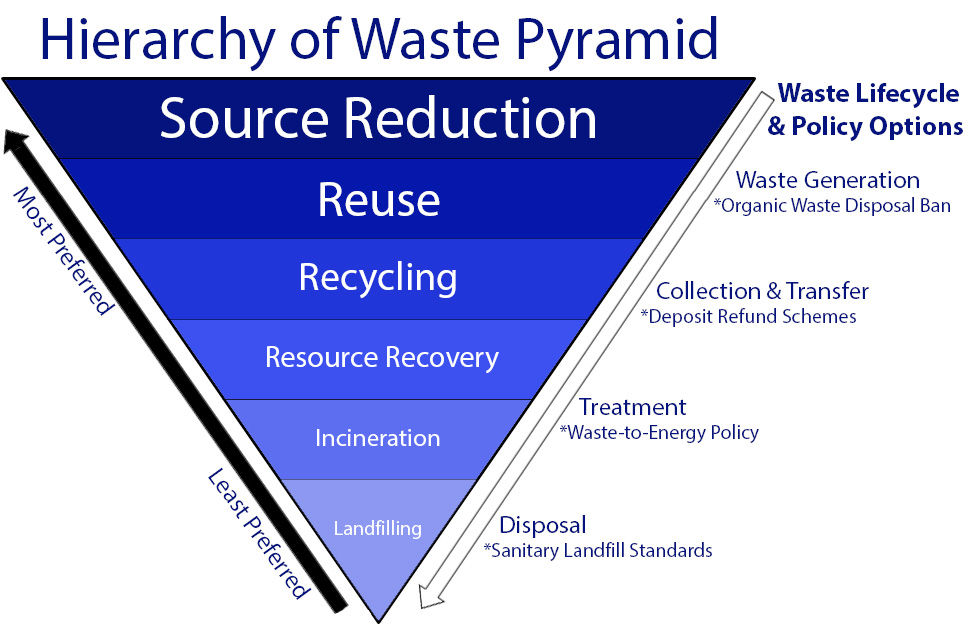

While governments strive to increase garbage collection rates, close illegal dumps, increase basic sanitation coverage, etc, there exists an opportunity to simultaneously lower emissions and achieve sustainable development benefits from waste management processes. The “Hierarchy of Waste Pyramid” explains the preference for waste prevention and minimization through reducing waste at the source or reuse and recycling efforts as opposed to final disposal options through incineration or landfilling. Local governments struggle to keep up with the higher demand to properly manage waste and have historically relied heavily upon the least preferred methods; however, there are several policy options that not only help to reduce the amount of waste produced, but also curb harmful emissions released during the disposal process and can contribute to economic development.

Organic Waste Disposal Ban – When organic matter is disposed of in a landfill, it undergoes anaerobic digestion, decomposing materials without oxygen to produce methane. However, if that organic waste is banned from landfills and instead diverted into composting projects, the amount of methane released from landfills would be significantly reduced or even eliminated, as composting is fundamentally an aerobic process. Composting can reduce GHG emissions (even more significantly than landfilling with energy recovery systems), act as a important carbon sink, reduce the need for irrigation (application of compost can reduce the need for compost by 30-70 percent), and reduce the need for petroleum based chemical fertilizers (use of compost can reduce the need for fertilizers for vegetable crops by 33-66 percent).

Deposit Refund Schemes – In this case, products made from recyclable materials such as plastic, glass and metal, carry a surcharge that consumers can reclaim if they return these products to reclamation centers, instead of throwing them away. Through this scheme, waste generation is discouraged by providing a small financial incentive to recycle. While the refundable deposit charge is generally quite small, the success of these programs in decreasing waste and increasing recycling rates has been encouraging

Waste-to-Energy Plants – Waste to energy facilities offer countries an alternative method to landfilling, are a viable source of renewable energy and help to reduce a country’s carbon footprint. According to the EPA’s lifecycle analysis for every ton of waste processed at a waste-to-energy facility, a nominal one ton of carbon dioxide equivalents is prevented from entering the atmosphere. As the costs of these facilities come down and energy costs rise, waste-to-energy plants are becoming increasingly attractive.

Sanitary Landfill Standards – Creating standards for sanitary landfill design, construction, and evaluation is critical to achieving important GHG benefits and decreasing local health risks. Sanitary landfills can lead to good control of landfill gases (i.e. methane) and leachate, and limit access of vectors (e.g., rodents, flies, etc.) to the waste. Ensuring sanitary landfill standards are created and enforced is increasingly important as countries move to shut down open dumps and invest in new sanitary landfill development.

As CCAP continues to research applicable policy options and NAMA opportunities for developing countries, success stories in various sectors will be showcased.

Comments